Minimum prices would address farmers’ concerns that they are being short-changed by buyers. But it would be a recipe for overproduction.

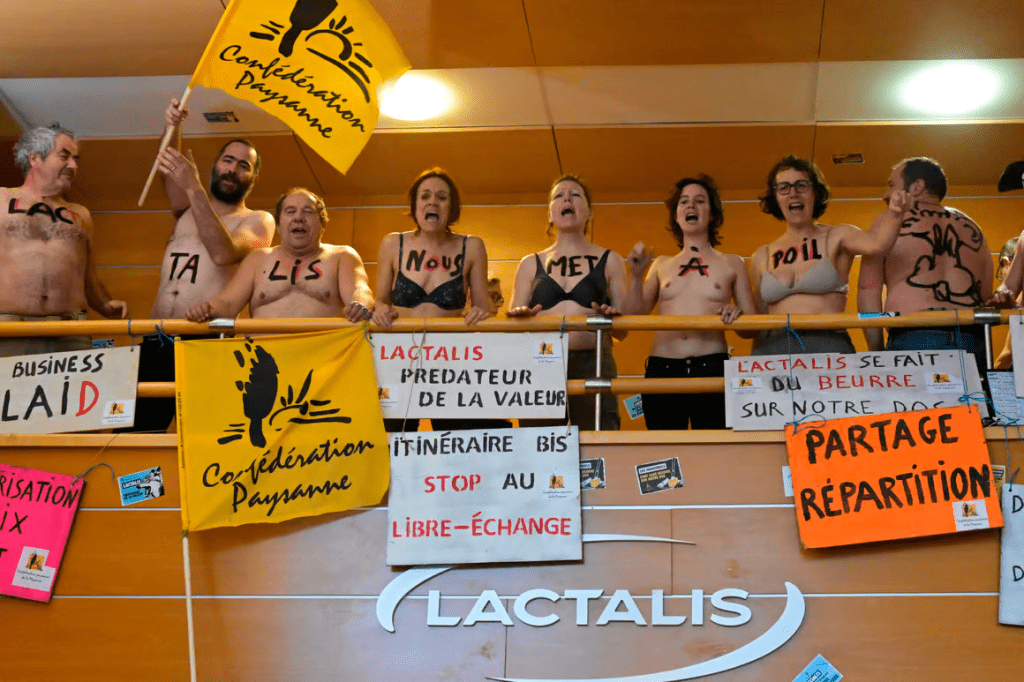

Farmers recently occupied the headquarters of dairy giant Lactalis to protest at the prices it pays for their milk | Damien Meyer/AFP via Getty Images

PARIS — Alexandre Vialettes and his 300 sheep feel ignored.

Half of the milk he produces near the village of Saint-Jean-et-Saint-Paul, in the south of France, is collected and processed by dairy giant Lactalis, at a price he is unable to influence.

Vialettes, who also makes his own blue cheeses, doesn’t know where his milk goes after it’s loaded onto a Lactalis truck. But he’s sure of one thing: it should have cost more.

During negotiations last year, a producer group that he is a member of had to accept the price proposed by Lactalis, despite resorting to a French law which seeks to ensure that farmers can receive fair prices for their produce.

After another supplier group agreed terms with Lactalis, Vialettes and his partners sought mediation — as the so-called Egalim law foresees — hoping to get a better deal that would cover their production costs. To no avail: the mediator said they should take Lactalis’ price or leave it.

“Lactalis is not the only bad guy. All the big groups, whether cooperative or private, behave the same way,” said Vialettes.

The bitter experience of farmers like Vialettes is one reason behind widespread protests this year — although much of their fury has been directed against the European Union’s green bureaucracy and competition from cheap imports. Their grievances have reignited a political debate in France about whether to guarantee minimum prices for produce. President Emmanuel Macron has emerged as a late convert to the idea — drawing fire from left- and right-wing opponents who accuse him of stealing their policies.

The debate raises the specter of a return to outdated price-support policies that may do little to alleviate rural hardship — and could instead stimulate overproduction and a return to the “milk lakes” and “butter mountains” of yesteryear. These forced the European Union to reform its Common Agricultural Policy, a farm subsidy program that eats a third of its budget.

‘Predator of value’

Lactalis, owned by the secretive Besnier family, has come a long way from its origins in the 1930s as a small camembert-maker in Mayenne, western France, to now being the world’s biggest dairy. During that time the company has repeatedly enraged farmers, who see it as the ruthless archetype of Big Food.

France’s latest round of agricultural protests have been no different. Farmers occupied the company’s headquarters last month. Others blocked a Lactalis truck and redistributed its milk to local farmers in the Haute-Saône department. Anger even reached the Salon International de l’Agriculture, an annual farm show, where protesters attacked the Lactalis stand.

“We have targeted [Lactalis] as a predator of value,” said Stéphane Galais, a dairy farmer in Brittany and representative of the Confédération Paysanne, a left-leaning farmers’ union that organized the demonstrations against Lactalis.

“This company reported turnover of €28 billion in 2022 and is making a profit. At its head you have two brothers and a sister who are billionaires. It is a company that doesn’t agree to pay its farmers properly, to pay them a price that covers the cost of production, wages and social protection, but which is raking in record profits,” he told POLITICO at the Confédération’s stand, which was decked out with posters attacking big food groups and free trade deals.

Pierre Maison, who produces raclette cheese in the Alpine department of Haute-Savoie, agrees.

“The farmer risks having little power. In a situation of quasi-monopoly, they dictate the price,” he said.

In his region, small dairy cooperatives have been fighting against Lactalis, as the company buys up shares in local dairy cooperatives producing reblochon cheese.

“We should not mix up the actions of agricultural trade unions with negotiations that take place within the framework of a private legal contract with a producer organization,” Lactalis said in a written response to a request for comment from POLITICO. “As soon as there is a disagreement or tension between the parties, communication is exacerbated, as it is a lever in negotiations.”

Lactalis said that prices were influenced by the fact that half of the cow milk it collects is processed or sold outside France, where prices are lower — and currently falling. It said it had raised purchase prices by 30 percent over the past two years, and paid more than its rivals in 2022.

The company reported a 14 percent decline in profits in 2022 — its net margin was just 1.4 percent — and these are re-invested in the business, the dairy giant said.

Macron’s recipe

The French government has tried, in response to the protests, to deflect the blame onto large food companies, promising better protection to farmers in their negotiations with processors, manufacturers and supermarkets.

Prime Minister Gabriel Attal has promised a fourth version of the Egalim law by summer. Economy Minister Bruno Le Maire has meanwhile announced stricter controls to ensure that current rules to strengthen the bargaining power of farmers are effective.

He has also threatened to fine two central purchasing platforms — through which retailers jointly buy products to get better prices — accusing them of not respecting the legal timeline for price negotiations.

Macron has passed three versions of the Egalim laws with the goal of strengthening the hand of farmers in negotiations with buyers, empowering them to propose a starting price based on reference indicators that reflect production costs.

Farmers complain that the law lacks teeth.

“It is absolutely useless,” said Vialettes, the sheep farmer, calling on the government to “use the stick.”

Under pressure from the protests, Macron has decided to go further. During a tense visit to the Salon, he proposed to set in law sector-by-sector minimum prices for farmers to sell their produce to the food industry.

Macron’s proposal for a price floor was widely perceived as a U-turn after his government repeatedly rejected similar proposals from the opposition, labeling them as Soviet-style anti-market measures.

It also raised eyebrows in his own camp.

“The announcement on price floors was not very useful,” said one lawmaker from Macron’s party, who was granted anonymity to speak freely. “The word is not a good one,” the MP said, saying it would be better to talk about an “index price” to avoid associations with flawed EU policies dating back to the 1980s.

Milk lakes and butter mountains

Unsurprisingly, supermarket chains didn’t like the proposal. Michel Leclerc, chairman of the eponymous supermarket chain, called it “bullshit.”

Experts have more fundamental objections.

“The EU had a system of high minimum prices for food products in the 1960s through the 1980s which led to the creation of food surpluses, high budget costs, and dumping of surpluses on third country markets,” said Alan Matthews, professor of European Agricultural Policy at Trinity College Dublin.

The resulting milk lakes and butter mountains would likely reappear if Paris winds back the clock, several experts have warned.

This wouldn’t just encourage overproduction, but also more environmentally-destructive farming, with higher chemical use, water-hungry irrigation and intensive livestock rearing. Then “we would have to destroy” most of the surplus, argued Matthews, “because since 2015 we are no longer allowed to subsidize exports.”

EU trade negotiators have just limped back from the World Trade Organization’s ministerial conference in Abu Dhabi after days spent fighting India on this very issue. New Delhi’s anti-hunger stockholding program has encouraged overproduction, agricultural sprawl and the dumping of rice and wheat on foreign markets.

The winners of price floors are often big industrial operators. If the floor price is too low, smallholders go bankrupt while larger outfits gobble them up. But if it is too high, then the largest farms reap fat profits at the expense of food makers and sellers. “This would be a huge icing on the cake,” said Matthews.

Spanish blueprint

For Maison, the Haute-Savoie farmer, France should take inspiration from neighboring Spain, which has turned the EU’s directive on unfair trading practices (UTP) into an important shield for agricultural producers.

Heralded by farmers from Namur to Naples, the Spanish version of the UTP law is the strongest in Europe. It allows for anonymous reporting of rule-breakers, foresees penalties of up to €1 million, forces greater transparency in contracts, and creates observatories to monitor product-by-product margins.

“It is only in Spain that this law has been effective and actually made a difference in the price of the farmers: it actually obliges each link of the food chain to cover its production costs, starting with producers,” according to the European Coordination for Via Campesina (ECVC), which represents small farmers.

The European Commission is currently running a survey for farmers as it prepares to revise the UTP directive. While Macron has called for a European version of his Egalim law, Brussels is more likely to look to Madrid for fresh ideas.

It is a complex debate that will reverberate about the halls of power as politicians try to re-establish order in a supply chain that is hurting farmers like Alexandre Vialettes.

“If we stopped supplying milk, the dairy industry would no longer exist, supermarkets would no longer exist,” he told POLITICO. “But there is a reversal of beliefs that makes us think that the distributor and the industry are the most important.”

Source: Politico